Dan Zimmerman, A.C.E., was born and raised in California. You could say editing is in his blood. He is the son of legendary editor Don Zimmerman, and his twin brother Dean, and younger brother David are both editors. The Zimmermans cross the fourth dimension as his sisters Dana and Debbie are also in the business. Together they are sometimes known as The DZ Seven.

After watching his dad do edit all those years, Dan enjoyed the craft and just fell into it. Don got Dan an interview at Pacific Title and that’s where he started in 1991. He worked there for a summer and then did a little bit of sound work with Dimension Sound where his hours began to count towards a union card. He eventually got in the union and joined his father in 1995 on The Nutty Professor and was his assistant for 11 years until he got his first break cutting The Omen.

Remembering how he got his first big job, Dan said, “We were actually in the middle of a show, on Fun with Dick and Jane, it was one of those things where he called to obviously get the whole crew back, including my dad, and we weren’t available. Big D (Don Zimmerman) had suggested that he could look for another editor for him and because we had known each other for so long John had asked if, either myself or my twin brother Dean, who also is in the business as an editor, was ready to make the jump, to take the chair. Yea it was kind of cool, but it was weird because the dynamic of, because my brother started working for my dad first, and whatever, I was totally like, hey, it’s yours if you want it man, you were here first. But he was engaged that year to get married and so it kind of didn’t work out, or he was having some kind of turmoil with it, and I was like, dude, it’s whatever, it’s your decision, you want it it’s yours. Initially he was like, yeah, I’m taking it and then the next day after probably talking with his fiancé, and just realizing that he would be gone at the time they potentially were going to get married, and the stress of just cutting your own first show, he was like I think I’ll wait. So yeah I kind of just jumped into it”.

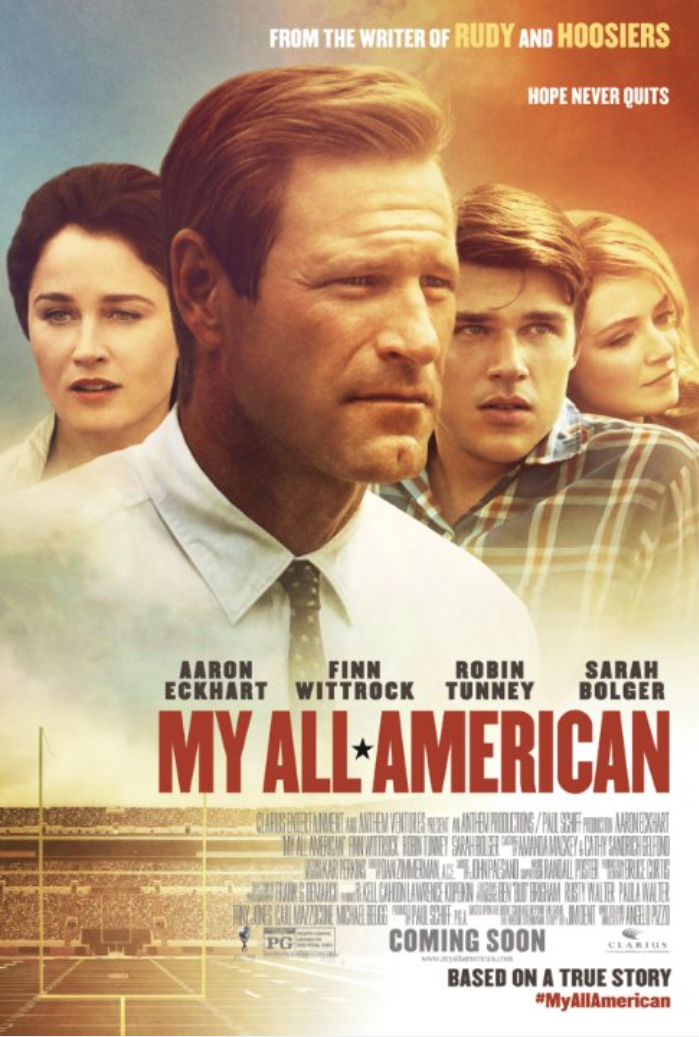

Cutting A TearJerker: My All American

My All American is a sports biography about Freddie Steinmark, an underdog on the gridiron, who faces the toughest challenge of his life after leading his team to a championship season. Director: Angelo Pizzo and stars Aaron Eckhart, Finn Wittrock, and Robin Tunney.

Jacobson: I woke up and first thing in the morning I queued up My All American. Well, I don’t know if I was still in sort of a dream state or what, but I found myself crying like a little baby, early, like within minutes practically, but what I realized about this film was it didn’t stop there. I was crying again very soon after and so I decided to count the times that the tears were shed. I found that it was probably five times in the first couple of reels. I don’t know what was going on with this but that film is a tear jerker and you, my friend, are the master tear jerker editor. Tell me about this movie you cut called My All American.

Zimmerman: My All American, which for me to date is, besides working with my dad, was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had in being an editor just because Angelo Pizzo is a sweetheart and literally from top to bottom, from the producer to finance, my crew, everybody was just amazing. So it was really a very sort of special project to be a part of and it will probably always be closest to my heart, I mean right now, because just the story itself. But I think in anything, you know, it’s like there are some of the parts of your career where you feel like if I had to do it all over again maybe I wouldn’t have done that, or maybe I wouldn’t have gone down that road, maybe I would have waited because something else might have come up. But, by and large, I’m really happy with the career path and where I am currently. At the end of the day I just really love working with great people and with people who share the same enthusiasm as I do about coming to work every day.

It is a very emotional movie and it started with reading the script. I was actually hired pretty late, I was only hired maybe a week before they started shooting because they were sort of courting another editor but he was doing another movie and he was waiting for production to really give him the green light and once they did he unfortunately had to back out of My All American. They kind of were hitting a scramble and my agent got wind of the fact that they needed someone and put through my name because I had played football and I was a really big football fan. More importantly I think I knew Austin a little bit, I mean when I went there I fell in love with it, it’s a great town, I became a mini UT fan. So when I got the script they were like read it as quick as you can. I got it in the morning, I downloaded it, printed it out, read it, and by the end of it I turned to my wife and said, honey, book me a ticket to Austin right now because I didn’t want to have a skype interview call, I wanted just to show up in person.

I called my agent and I said hey I’m booking a ticket to Austin right now, they’re like wait, wait, wait, hold on, just get them on the phone. I’m like, well if you don’t get me on the phone in like two hours, I’m outta here and I’m going there because I want to show them my convictions for wanting to do the movie. So they jumped on the line and it was Paul Shiff, who was the producer and Angelo and I think I just verbally attacked them. At least that’s the way they felt when we laughed about it months later because Angelo said Dan, after your skype interview, and we had done a lot of interviews, I turned to Paul and said either this guy is completely crazy and going to kill us, or he’s the absolute guy for the job. Thankfully it was the latter. It was like, I was crying in the script man.

At the end of it, because even though I was a mini Texas fan, I didn’t know Freddy’s story and I didn’t know that there was actually a monument that the player’s pay tribute to every time they walk onto the field. So it was really touching and it was just something that I knew I had to be a part of. But, yeah it’s an emotional movie man and I love the idea of making a movie that was kind of timeless in a way. It just seems like it’s a movie that no matter when you can see it, if you saw it 10 or 15 years ago if it was made, or in 10 or 15 years, I think you’re going to ultimately have the same reaction just because of who Freddy was and what his story was really all about.

I think the hard part is a lot of people say that there’s not a lot of conflict in the movie which kind of makes it very one noted, but that’s who Freddy was. He kind of was the kid who didn’t have any flaws, which is he went to church every day, he was raised by a wonderful family to be very loving, caring, supportive. That’s the way he was with all his friends. He sort of led by example not by, sort of, personification. He was kind of like the ruby, but didn’t make a big deal of it. So ultimately, even with this tragedy, he maintained his optimism about wanting to live, or not wanting this to actually happen to someone else. That he could actually end up helping someone without even helping himself kind of thing.

Jacobson: The football footage was incredible.

Zimmerman: Yeah and you had real players really hitting each other at full speed and I think they captured a lot of great imagery.

Jacobson: Totally choreographed to make the film work.

Zimmerman: And by the way, it was really tough because these games and these plays happened so one of the biggest challenges was being able to maintain exactly how the play happened but also use it to tell your story as well. So you can manipulate it a little bit but, all in all, players that are still alive that played in these games remember exactly that play and there were so many of them that actually said, omg, it was like reliving being on the field that day, which is I think the ultimate compliment to both the people that shot it and acted in it and ultimately the way it was presented. So many times my assistant would come in and go, dude, why are you out of breath? And I’m like, I don’t know, I’m getting a football montage.

Just kind of getting really emotionally connected to it and so many times they’d come in and I’m like kind of doing that or looking away, my eyes are all red, and they’re like, oh you’re watching that scene, okay got it. Again, it’s just a powerful, it touched me in a very personal way, the script, because just being a real fan of football and playing football and wanting to play football, just having that kind of passion for anything. Right now that same passion for me is in what I do. It’s just so relatable. It was hard for me to believe that anybody that saw it wouldn’t, that there wouldn’t be something that they could pick up on that could relate it to their lives in a way that would touch them, which is one of the most powerful reasons that I did the movie and what drew me to it.

Jacobson: Well it certainly worked. I think it was amazing to reach those levels emotionally and I’ve heard so many times that comedy is the hardest thing but I think maybe tears are harder.

Zimmerman: Yeah, I mean, because people truly when they go to theaters do ultimately want to laugh or be entertained, but I think you might be right. Some of the most powerful moments are the ones that affect you enough to actually get you to kind of go to a very vulnerable place.

Jacobson: How do you do that as an editor? How do you get them there?

Zimmerman: You know it’s so funny man, I think you just have to feel it. Again, with editing, it’s all about feeling. You can be top structures and how to cut things together to kind of look out for composition and all that stuff, but I think ultimately when you’re telling the story it’s coming from you and that’s what I think people don’t realize that us as editors we’re putting part of us into what we’re watching and into what we’re sharing and how people view it. I think really My All American, which is why I think it will always be one of the movies that is closest to my heart, is that I really did put everything emotionally that I could into the movie because really that’s kind of how I am.

I’m an emotional guy. I do wear it on my sleeve sometimes. I’m a patient person, I think. But at the same time I have no fear of crying in public or anything like that if it really comes to me. It’s funny I always said if I ever got nominated for anything or whatever, I’m not 100% sure that I would be able to actually get up there and do it. I might have to send like my wife or someone else because I think I would just be a mess because so much of my success is not just me, it’s the people that surround me, it’s my life, and all that stuff. It overwhelms me sometimes especially in those kinds of moments. Even in doing these kinds of interviews, I feel very sort of like, very blessed in a lot of ways.

I don’t think you ever get used to sharing yourself with people but I always feel like if I can touch, or if one person is interested in what I have to say, or it motivates them to want to do something they want to do, then its 100% worth it to me.

The Generation Gap

Jacobson: Do you take to technology easily or do you go kicking and screaming? Seasoned editors have been able to adopt or they die.

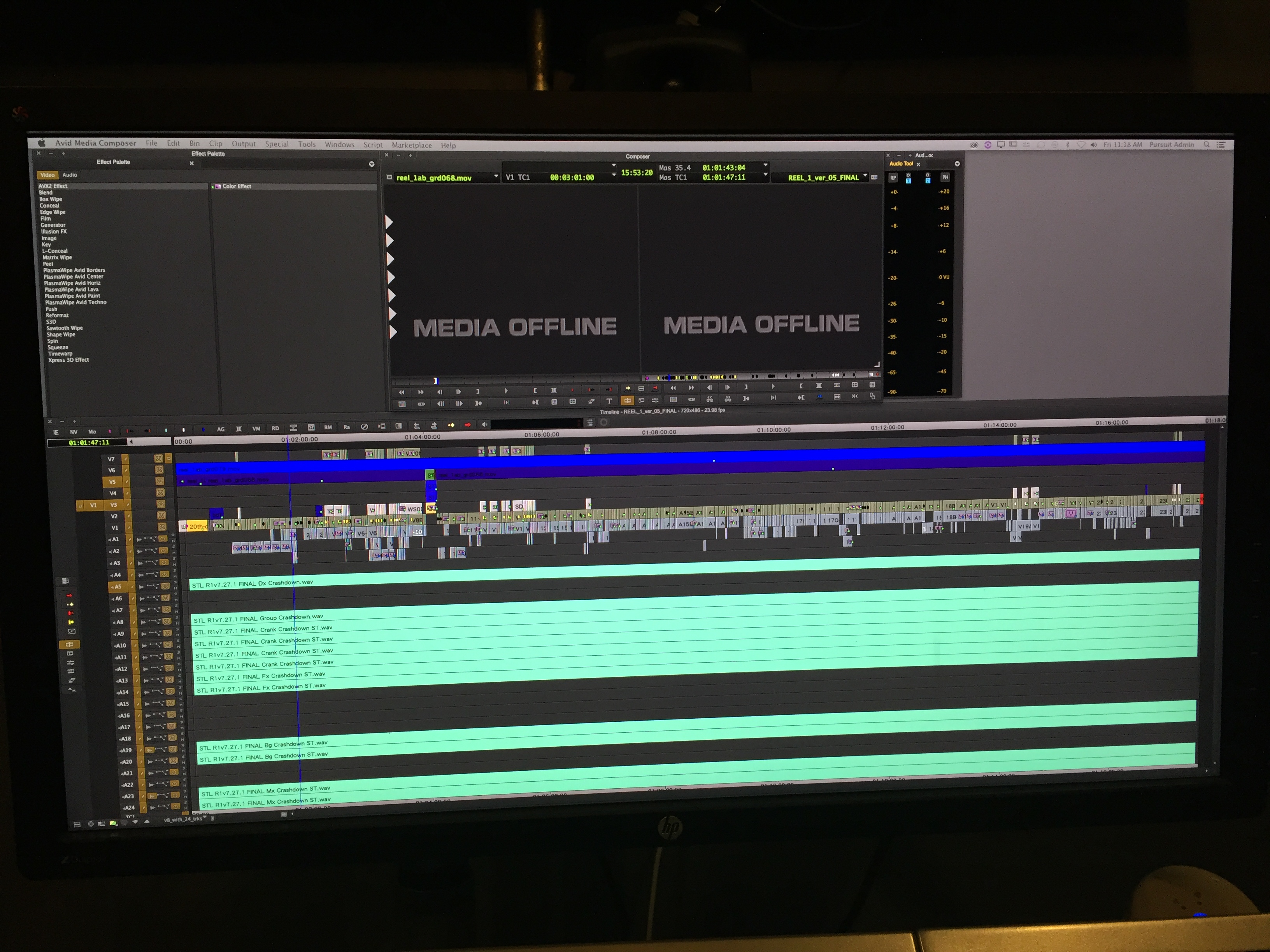

Zimmerman: No, you know, it’s one of those things where I really love technology and I love to keep myself up on it, but by no stretch of the imagination am I an expert at it at all. I’m an old guy compared to some of these guys now. I used to say that about my dad and now here I am, 41, and I’m the old guy. You kind of like have to keep yourself in the loop if you want to keep yourself relevant. I mean obviously you can’t always dictate what system you’re using because if you’re working on a studio picture typically they’re going to want to try to figure out, you know, or they have a system in place, or whatever. I ended up on an Avid Media Composer because I went back to 20th Century Fox and worked on a show that was already Avid driven.

Jacobson: There is a wide spectrum of ages working today. 20 year old Millennials to Baby Boomers who are in their 60’s. I was wondering if you’ve had any experience working for generations of people and how that affected you as an editor.

Zimmerman: You know, absolutely, like when I started, obviously working with my dad who is very much older, but we were working with Tom Shadyac who was this up and coming director, a young kid. And Jim Carey, and these guys were, at the time on Ace Ventura these guys were sort of legends in the business at the time, so you kind of grow up with them a little bit. But everybody around me, especially when you’re involved in the studio systems at such, for me at such a young age, a lot of the producers and a lot of the executives were my dad’s age, or are my dad’s age, so they were older.

I think one of the biggest benefits of nepotism is that you are recognized, and being a twin, my brother and I get recognized a little bit more when it’s associated with my dad because we were two little kids running around. We were these little fat pudgy kids running around and always making noise so people remember us just from that. It’s funny because I always say, when I see people I know, either on the lot or on the street or whatever, I always know how I know them, or how they know me, based on what they call my dad because my dad’s had a couple of nicknames throughout his years and back in the early days when he was working with Hal Ashby and Warren Beatty and all those guys, he was known as Donny, they called him Donny for some reason. Once that sort of transitioned a little bit when my brother and I started working with him, we didn’t want to call him that because he was our dad but we didn’t want to call him dad at work so what do we call him? We’re like well you’re Big D. So we ended up calling him Big D and that sort of stuck for a little while. So I always can gauge where, generationally where I am when someone references my dad by his nicknames. It’s amazing how much you can pick up from that generation, and I was very lucky to be part of, sort of the domineer editing transition, the electronic transition.

Jacobson: Right.

Zimmerman: Because I started in film when I was assisting my dad. He was still cutting on film and so you would do the recon, and you do all the dailies in film, and you would do all the conforms to the reels, and all the changes and all that stuff. Then we basically, we incorporated together the transition into telecine, the print and the mag and then just telecine from the negative and whatever. My dad, much like me, loves to learn and he started on Lightworks and then we actually stayed on Lightworks, and variations of, into Heavyworks, and stuff like that, for the first part of the late 90’s and early 2000’s. Then really Cat in the Hat was really the first movie we had cut, or that my dad cut on Avid Media Composer. Once he learned Avid he’s primarily stayed with that until now.

Jacobson: So both of you were able to make the transition from film to digital.

Zimmerman: Yeah, and it’s funny because, and I think one of the reasons why he liked Lightworks so well was because it had that big controller with the Steinbeck kind of shifter, and the big buttons, I think he liked the big buttons because they reminded him of a Kem. So I think it was just an easier transition for him, but he picks up things very quickly so it wasn’t a huge issue. For him it was just another tool to do the same thing which is to ultimately tell the best story you can. So he never let the fact that it was technology hamper him in wanting to learn it or utilize it in his profession.

Jacobson: It’s interesting, filmmaking, Hollywood in general, is a family business in a lot of ways. I know many families that have, their entire family is involved somehow in the business. You don’t seem to be afraid to talk about nepotism… I actually tried to talk to someone once about nepotism and they got very defensive and tried to push back about it.

Zimmerman: Oh yeah. I do know people that way as well, but for me nepotism is why I’m here and I never let that be forgotten and I totally appreciate it. I try not to ever take it for granted because it’s one of those things that, you always want to be your own individual, of course, you always want to separate yourself from oh that’s Don Zimmerman’s son, or that’s Donny’s kid. But at the end of the day you are who you are and you’re going to make the name you want to make for yourself. For me, I love my dad and I still have such a great relationship, he’s one of my best friends ever, and he taught me everything I know. So, every day that I get to come to work and do my craft and try to do it better every time, I’m just ultimately paying homage to him. It’s something I don’t ever take for granted, I love the fact that I have my dad’s name to kind of live up to and to carry on. That to me is a great thing, a very positive thing. I didn’t want it to ever be the negative.

Jacobson: Did you find that maybe you had to work harder or you tried harder when you were a kid? Competition with your family?

Zimmerman: Of course, I think you do anyway. My family is really competitive anyway. With a lot of boys and everything you’re always competitive. But I think that there’s also a real respect. I always tell everybody we truly are not curing cancer, we’re not doctors, we’re not changing the world in that regard. We’re not saving lives. But we are providing, you know, if you can come to your job every day and love what you do, it doesn’t matter where you came from or who your dad is, or who anybody is, that’s a win. I come to work every day with the same attitude which is I’m so lucky to be here, I’m getting paid to do exactly what I love, it’s super creative, and by and large the business has amazing people in it and you meet them every single day

Jacobson: Do you work with temp sound or do you try to use your own sound in your head to gauge your rhythm and pace?

Zimmerman: My process is one that, I sound out everything like to the point where I get a little bit obsessive. I start cutting foley and my assistants then very quickly tell me that, like hey I’ve got 5 more bins for you full of scenes, and I’m like, oh yeah I forgot about this. I truly find that it helps me gauge exactly that, pacing and rhythm, and ultimately where you need music and where you don’t, because a lot of times editors, I’ve found through conversations, use very little sound but just trying to find a piece of music that can get the scene working. The one thing about that, because I used to do it, is that you then end up when you put the timeline together, you find, Oh my God my whole timeline is music. Then you’re trying to figure out how to get rid of music but then it feels weird because you’ve gotten used to hearing it.

Jacobson: Temp love.

Zimmerman: Yeah total temp love. So I actually do the opposite which is I’ll cut a scene just with the production track and even in its roughest form, even if I totally dislike it, I’ll sound it out totally so that when I change it it maintains all that stuff because I feel like whatever tape you choose it will still work, you just have to figure out how to manipulate it. For me it gives me more of a sense of how a scene can play with nothing and then if it really does require a queue because of an emotion that you want to try to get across, or if the scene is just sort of a necessary scene to the story but it’s just taking a little bit of time so you kind of want to help it along and make it feel a little faster than it maybe is playing with nothing on it, and all the things that music does, so I do that music last actually.

I find that it really does help create a better full timeline when you put the assembly together and you kind of realize, oh okay cool, it seems like I’m not overdriving this movie with music. Sometimes movies do require that but more often than not we’re always looking for places to maybe strip it because I think there’s a real beauty behind watching a scene with nothing on it because I feel that you kind of start to lean in just a little bit more, pay attention a little more, and it just becomes a little bit more impactful.

Jacobson: Do you find yourself recutting once you get the real music in or do you think on the average you nail it?

Zimmerman: No, I never nail it. It’s funny because I do this analogy a lot, Hitchcock always said films are never finished, they’re abandoned. I feel that way the entire cutting process. I always feel like I never really nailed it. There are different scenes that you’re proud of like where you cut it the first time and you’re like, damn I really feel good about that. But it’s the natural course of collaboration. When you finally show it to your director and you start to get other input from different people. Things change and there are many scenes that I cut that are amazing scenes that are just that, amazing scenes as themselves, but just didn’t fit within the movie as it was or at all. That’s the one thing that’s so amazing about our profession is that every day it’s something different; you’re never going to do the same thing twice.

Jacobson: You seem to really get into your projects.

Zimmerman: Maybe, I mean, yeah I think to be good you have to be. I think you have to be emotionally invested in it. Growing up, I mean obviously being that my dad was in the business and he worked with Sylvester Stallone for a lot of years and he did Rocky 3 and 4, I think that’s actually where I really came up with loving action movies. And really, ultimately, those montages, or those training montages for those two movies, to me like stand the test of time. Even though they were done in the 80’s they still are relevant. They are phenomenally cut. Back then when they were cutting on film, to do all of those cross dissolves and super impositions and stuff back then, that’s when you really technically look at it, it’s amazing and really cool. I think he really did influence my sort of trajectory into what I wanted to do, to be in action and stuff. I’m really just a movie fan in general.

I love watching movies. I love being involved in movies. I love going to movies. So I think that all plays into it but yeah I definitely get into it. During action sequences, I work standing up and I have for the last 3 or 4 years because I really felt like it’s actually helped what you do because you can stand back and kind of move around. I think that’s why sometimes when you really get into it and you’re cutting this really tense scene, I find myself leaning so far in I’m like this far away from the monitor. But then you know it’s working. I always feel like if you’re investing and you’re cutting it all day long, every day, if for some reason you’re still doing that then I think you’ve got something that works. So I totally let method play into it because I feel like it really gauges or gives you a gauge of what is working and what’s not, for pace, or for whether a scene is relevant or not.

Jacobson: Do you multi-cam at all? How do you use it?

Zimmerman: I group every clip. Working with my dad, even in the Kems, we parallel synced all of his dailies, which basically means that for every camera they shot on set we would have the film for. So our split reels would be, we’d have like, if they shot 5 cameras we’d have all 5 cameras and we would ask them to do comment slates, and even if they didn’t more often than not you could find a sync point. So when my dad was on his Kem he could have one piece of mag that was in sync with all 5 cameras. Back then he had three 8 plates that were combined. It did sort of a horseshoe kind of thing. But I don’t think there’s a room big enough to have more than that. These were big machines back then.

So the idea of parallel synching dailies was just innate to what we were doing because that’s the way my dad liked to work. That’s why I think multi-cam always was not a problem for me. On Die Hard, that whole car chase sequence they shot 10 cameras every time. So you can’t watch single cameras…it would kill you. So yeah multi-cam is awesome. I add it to my timeline so if there’s ever a time when a director is sitting with me and he’s like, show me another camera what does that look like? You just hit change camera and boom it’s right there. It’s very essential to my work flow.

Jacobson: Do you set up your own Avid? Do you have a certain workflow? Do you have assistants? How do you put a project like this together organizationally?

Zimmerman: Yeah basically my first assistant has been my assistant for a good number of years now, three or four, but every assistant I’ve ever had, since 2005 when I started, I always kind of train them how I was trained because that’s how I want it to be cut. So the way I like to have my dailies organized, definitely group clips if there’s multi-cam. But I always told my assistants what my dad told me when I first started, because back then he would cut in Kem rolls so you’d have your wides, your mediums, your close-ups, all that stuff separated so that he could easily grab the roll of film that he needed. But he always told me to organize the scene the way you would cut the film.

So reference the script, because you know the footage before I do because you’re seeing it because you’re checking dailies, and organize it the way you would potentially cut the scene. So if the script says it starts on a close-up of a wide and pulls out to reveal your villain, whatever, then that’s what I would do. I wouldn’t use the master as the first clip up. I would put it sort of how I thought the scene would be cut whether that’s starting on the close-up or starting on a wide-shot. So I never really stuck to the standard of wide, medium, close, insert kind of thing.

Mostly follow your instincts. I tell my assistants your instincts are never going to be wrong because those are yours and if I organize it differently that’s just because they’re mine. But more often than not, they quickly realize how I like to cut things and I never have to change my bins. So I’ve had very good luck and my assistants are awesome. One of the things I credit my dad most with is being a teacher’s editor. He seemed very collaborative and he always would call us in to watch a scene he cut, or to just get our opinion on something, a line or a performance. To me that was the invaluable part that I wanted to impart on my crews. So I do the same thing. I’ll cut a scene and I’ll call my assistants in and show them and get their input. I love being collaborative like that and kind of open. Like I said, you kind of do what’s been done to you. You try to always take the good and try to better on what you thought was the bad. That’s what I’ve been trying to do.

so interesting!