By: Mitch Jacobson, Category Five Studios | NYC

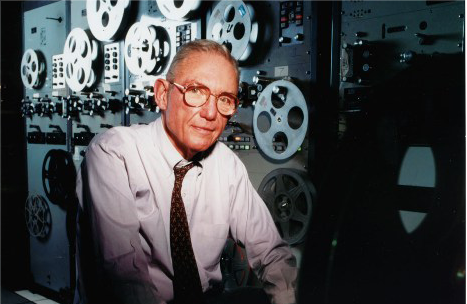

The geek in me feels like a groupie today except I’m not backstage at a rock concert. I’m at the historic DuArt Film Lab Building in New York City and the “rockstar” I’m here to meet is the legendary Irwin W. Young, 90 year-old owner and chairman of DuArt Media Services, a pioneering film innovator, angel-to-the-artists and colorblind engineer. He is the Les Paul of the movie industry and has a couple Oscars to prove it.

DuArt Film Laboratory Circa 1922

I’m here to explore filmmaking history and the early lab technology that Mr. Young and his family at DuArt developed.

The newly renovated DuArt Media Services featuring their historic contact film printer. (Click Photo to watch video of Irwin Young explaining this equipment)

Irwin Young’s passion is in the arts, but he was trained in chemical and industrial engineering and has been in the film industry his entire life. DuArt Film Laboratory started before he was born and most of his immediate family members are in the business….they practically started the film business dating back to WW1.

His father, Al Young, began as a film editor and documentary filmmaker working briefly in Hollywood. His film a “Fight for Peace” had a 1938 White House screening. He bid at auction and purchased a film developing business on west 55th street in Manhattan, naming it DuArt Film Laboratory in 1922. He ran the film laboratory, was a timer and was very much involved in the technology of the industry.

Early film processing deliveryman, Irving Rathner and DuArt truck.

Over the past century, and under Mr. Young’s careful watch, DuArt has processed film, performed color timing and created theatrical prints for some of the world’s most influential filmmakers. They have created or supported the development of the most critically acclaimed motion pictures of all time. Hit films like “Mighty Aphrodite,” “Forrest Gump,” “Philadelphia” and “Dead Man Walking” were all printed at DuArt for theatrical release.

The 80’s marked a turning point for DuArt as they embraced Super16 film processing and perfected a technique to offer extremely high quality 35mm blow-up prints, an important milestone that allowed lower budget independent films to compete in the worldwide marketplace.

Step Registration Printer used to print black and white separations to make Technicolor prints.

Groundbreaking films such as Robert Young’s (Irwin’s brother) Cannes Camera d’Or winner, Alambrista and John Sayles’ The Return of the Secaucus Seven gained world wide audiences. Barbara Kopple’s, Harlan County U.S.A. was able to qualify for an Academy Award and won the Oscar for best documentary. Important new directors such as Spike Lee, Susan Seidelman, Robert Altman and Errol Morris all benefited from the process of high quality 16mm blow-ups from DuArt.

It was this process and innovations like Continuous 35mm Processing Machine and a computerized system for negative preparation, timing, and color correction called The Frame-Count Cueing System that revolutionized lab work and led to the Academy Award for Technical Achievement in 1979.

From Black & White to Color Blind

Photo courtesy: Flickr | Ben Mortimer

“I didn’t find out I was colorblind until I was older”, remembers Mr. Young, “ I am red/green colorblind. Sounds crazy psychologically but your mind adjusts!

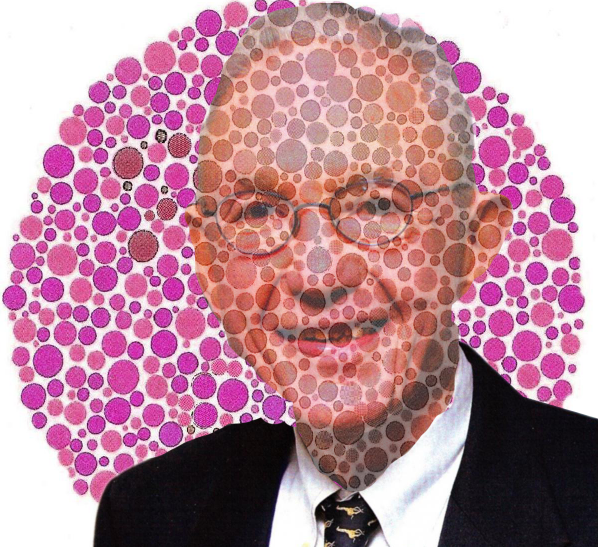

Irwin Young

Being colorblind couldn’t stop Irwin from working in the film laboratory business with his father, because film processing and timing was for black and white film. Colorblindness became a huge advantage when dealing with neutral colors, luminosity and contrast. Our eyes have cones and rods. Cones read the colors and rods read the density. Colorblind people tend to have stronger rods are more sensitive to changes in the black area of grays & blacks than most people. They also do very well in low light or nighttime lighting situations.

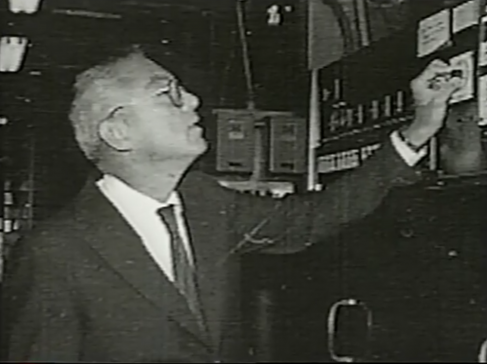

Irwin at the control panel of a processing machine in the lab at DuArt circa 1970

IRWIN YOUNG: “Being colorblind made me very attuned to black and white images in the area of contrast and how it looked or if there were any defects or problems in the film. Because I had this handicap, I was excellent. I had an advantage in my training because I didn’t have the color and my eyes are more perceptive to neutral densities”.

“In lab work, you weren’t really determining what the color was, you were timing it the way it was photographed by checking the exposure of the material. It was the creator that was determining the color. Your job is to create the image that he’s photographing not to create another kind of image. But theoretically if they’ve exposed their film right, then if you time it right, it’s going to come to the right colors and everything of what they envisioned on the set. So then you would print the light to make it look like they wanted it to look”.

Are you colorblind? Take the Test!

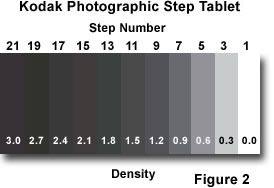

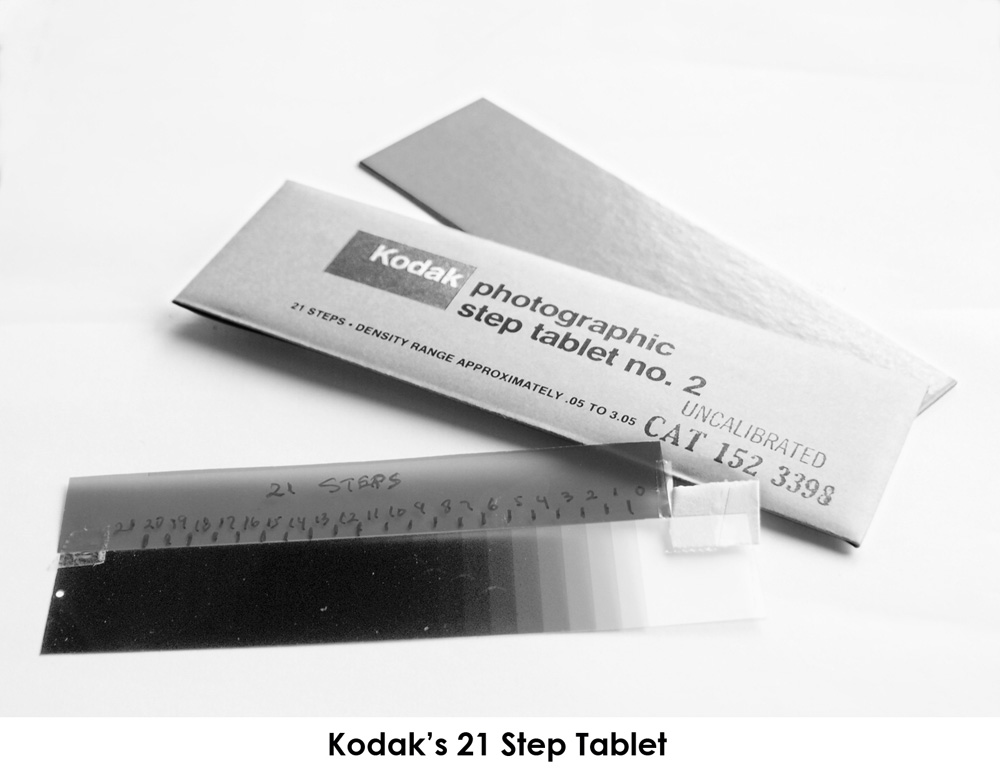

Gamma Strips in the Lab

“When you’re color blind you’re not really blind, and you see neutrals the same way. So we used neutral density strips called “gamma strips” to know the contrast we are controlling,” recalled Mr. Young.

A gamma (or density) strip is like a color chart that’s made by shooting a black and white image on color film. They would call them gamma but they were really density strips. It’s a color image but when you make a print it should be a black and white image. A gray scale is printed with a printer that has R, G and B lights, the RGB lights have to be exposed properly to create a neutral gray scale color with proper density. It was mandatory to run the gamma strips.

IRWIN YOUNG: “It was color film you would print. You were checking the neutrality image. You’re going from color to color. That’s the control so the chemistry is right and the exposure of the scale of light intensity is correct. You use the gray scale to keep it neutral and to make sure that when the negative film was processed, it would be processed at the desired contrast.

IRWIN YOUNG: “It was color film you would print. You were checking the neutrality image. You’re going from color to color. That’s the control so the chemistry is right and the exposure of the scale of light intensity is correct. You use the gray scale to keep it neutral and to make sure that when the negative film was processed, it would be processed at the desired contrast.

“You didn’t have the leeway as you have in the digital world to do almost anything because you had to be with the right density. You were more restricted in the laboratory as to what you could do and it was very important to work closely with the cinematographer.

“I would be in the control process department to make sure the positive and negative processes were correct and when they’re put the film together it produces a neutral scale so that that neutral scale can then marry the color properly. What I would do is put gamma strips through with the client’s film so you would look at the strips going through every hour and they would read the strips to make sure the processing is right.  I would go back to the gamma strips and check and make sure that everything was right. I think my eyes were very much into sharpness and reliability of reproduction.

I would go back to the gamma strips and check and make sure that everything was right. I think my eyes were very much into sharpness and reliability of reproduction.

“There were even strips made by Kodak so you’d match that the strips you were making were exactly like theirs were and you would keep checking and you would also make those strips yourself in your control department.

Processing Color

In the early 1950’s with Eastman Kodak’s introduction of color film, DuArt processed the first film in Eastmancolor negative. Mr. Young, together with chief engineer, Fred Bray and Paul Kaufman, was able to design and build the first color negative/positive processing machine and scene to scene color correction printer.

There were only two-color processes at first. Color films had three layers, red, green and blue sensitive, and it had to be perfectly balanced so, Eastman came out with the first three-color process negative processes where it had red, green and blue (the positive colors) and the dyes in the emulsions of the film were magenta, yellow and cyan (the subtractive or negative colors). They were the red-green, blue-green, and red-blue colors. When you put them all together you got neutral and it was all done chemically.

Negative record recombination to color positive print in 35mm three-strip Technicolor. Courtesy: John Kostka UCLA

The processing of the film required developing it in the right kind of bath structure and bleed rate to accurately recreate the color and contrast information originally intended by the cinematographer.

IRWIN YOUNG: “If the objects in the footage was shot gray, the print would be gray, if it were green it would be green, and if it was blue it would be blue, or yellow, cyan, or magenta, or whatever the combinations of the colors required”.

Printing & The China Girl

“You knew that if you had a certain mid-range timing, you got a normal image. That always had to do with the printers. They had to have enough light source and if you had a mid-light all of the other lights that they were using would give you a proper range for printing. The exposure of the neutrality relates to the exposure of the negative so you could get a different response for each color. The control process also let’s you repeat the same look or vary the color for multiple prints.

The vast majority of “China Girls” were white, but collectors have found some that were not. Courtesy: Peter Monaghan

“The printing machines had to be managed to be the same and they had to be set up on the basis of the proper gamma strip, an image and the “China Girl”: the color test footage used in the lab.

“So when you printed on each printing machine with the 25 light, or whatever would be your neutral light, it would all be the same on all the printers. You would adjust the level of the light on the printers so they would produce that kind of image; they would all be the same.”

“Kodak was very much involved with us because when we processed the chemical baths they had to be positive to be done properly and it had to be the same when you developed the negative. It was very important to be proper from day to day. There are ways of keeping the chemical baths normal by analyzing the chemistry of the bath. You would check the bleed rates and we would have strips going through all the time….the working baths should be the same. But in the film process, you just had to be very rigid in what you were doing with the physical process so there was no damage or anything to the film, or scratches, or dirt”.

For More on China Girls, Checkout This Page

Angel-to-the-Artists

With one foot in science and the other in the arts, Irwin Young strikes the perfect balance needed to succeed in the world of filmmaking. Early in his career he went on a mission to help the young filmmakers achieve their goals by offering free processing to film students and many other discounts to independent filmmakers all over the world.

He became a mentor and advocate for such directors as Spike Lee, Michael Moore, Barbara Koppel, Oliver Stone and a list that reads like a who’s who of film.

The main reason for Irwin’s endless support of the arts and the origin of DuArt’s amazing Super 16 enlarging technology started with his brother Robert M. Young.

Irwin and his brother, Robert Young with Michael Moore

“We needed Super16 and superior 35mm blowups for my brother’s films. It was a family affair but he should get the credit”, said Mr. Young.

Irwin receiving an award from Kodak.

Linda Young, Ang Lee and Irwin Young

The artist and the scientist

This technology sparked the independent film market and their films went on to win the Camera d’Or for Best First Feature at the Cannes Film Festival for Alambrista! and the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance for Children of Fate: Life and Death in a Sicilian Family.

It earned Irwin an Oscar in 2000 when he was awarded the Gordon E. Sawyer Award by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for technological contributions to the motion picture industry.

“In this world of technology, you need a group to make things

work, There’s no better relationship than between the scientist and the artist”

– Irwin Young

The full acceptance speech:

IRWIN YOUNG:”Images are a very important part of our lives and so we have to understand them. I came from a family of creative people but, I’m became an engineer by attitude. So, I can relate to artistic feelings. The work that I did with the artists helped me understand what’s important in life- working together so, I help the filmmaker”.

Irwin Young with Mitch Jacobson at DuArt Media Services in New York City (2014)

Mitch Jacobson is a part-time film history buff and New York City based editor/colorist. He is the owner of Category Five Studios and author of Mastering Multicamera Techniques (Focal Press).

I’m red/green colorlind too. Always nice to read about colorblind people using it to their advantage (or at the very least not to their disadvantage). Cool article Mitch!

Very nice Mitch!